The Anatomy of a Compounder

February 08, 2024

Key takeaways:

- Compounders are companies, that have the potential to deliver sustainable and long-term growth.

- We believe the biggest opportunity in equity investments is to look for companies that have the potential to compound their earnings over many years or even decades. However, simply buying the highest growing companies is fraught with risks.

- We emphasize sustainability of growth over magnitude of growth. We believe, identifying sustainable growth businesses is irrevocably tied to the holy grail of investing – namely compounding.

- If higher growth companies deliver on their estimated growth, the valuation profile would look quite different, with the most expensive companies today actually trading at a relative discount on valuations measures in 5 years’ time.

At its core, whether you label it value or growth, investing is about buying something for less than what it’s worth. But how should this be measured? The temptations for short-term performance measurement with the technological tools at hand today are substantial. Exact measurement has nothing to do with consistent investment success. Shorter term investing invariably becomes speculation, as it takes time for fundamentals to crystalize. Most research and most investors have a year-end focus. That is a result of human and institutional biases. At best, prevalent investment horizons stretch out 12 to 18 months. Investing with that shorter time horizon and perspective is a crowded and difficult space with only few creating consistent strong relative investment results. It is therefore critical to force yourself out of this trap of potential investment failure.

Higher Risk in Fastest Growers

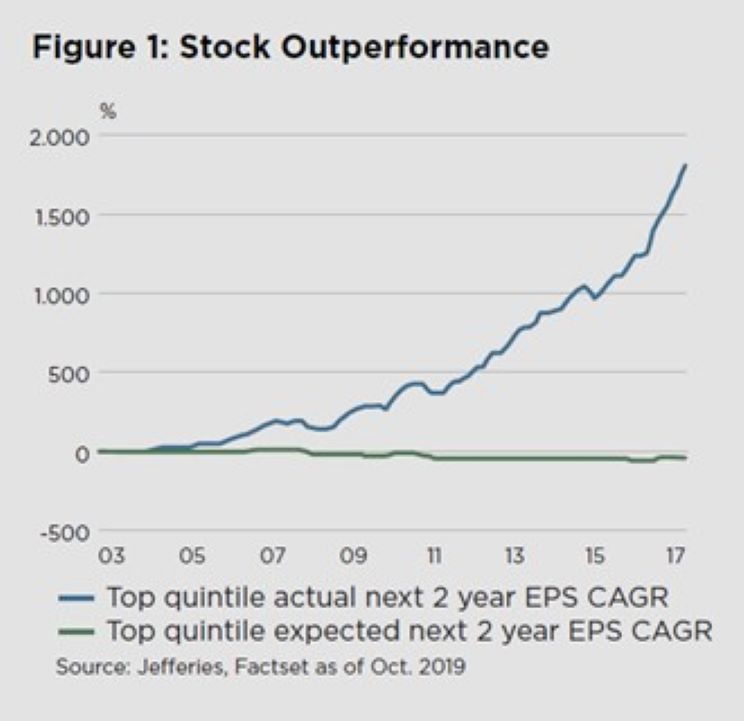

An interesting analysis, although only focusing on a 2-year forward horizon, (Jefferies, Micro strategy, October 2019) shows that, if investors had perfect foresight and bought companies that did go on to deliver the highest next 2-year earnings compound annual growth rate (top quintile), they would have strongly outperformed. The cumulative outperformance over 15 years from this “perfect” portfolio would have been 1798%. Obviously, investing in true growth companies is really rewarding. However, the main challenge of this approach is investors’ (limited) ability to forecast earnings growth correctly. This is where investors and analysts have struggled, because a similar backtest based on forecast (and not realized) next 2-year earnings growth showed significant underperformance over the same period. Simply buying the companies that are expected to grow earnings the fastest would have led to 47% underperformance – see figure 1.

This is because the highest growth companies (in the top quintile growth forecast basket) have on average not been able to live up to expectations and have witnessed the biggest earnings disappointments.

It is important to note what Miller and Modigliani concluded already back in 1961, namely that future value creation depends on the company in question being able to find projects that generate a positive spread between the Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) and the Weighted Average Cost Of Capital (WACC). That is how free cash flow for shareholders is generated. It seems so obvious, but occasionally the market gets the “growth-at-all-cost flu” like in the TMT bubble and more recently in the UNICORN bubble, after which we witnessed huge wealth destruction as valuations of companies like WeWork and Uber collapsed, just to mention two. At the end of the day, no matter how exciting the growth story seems to be, great companies for long-term investment must eventually generate a positive spread. Growth creates value only when the spread is positive; it has no effect when the spread is zero and destroys value when the spread is negative. Too many company managements and investors focus on growth without recognizing the need for a positive spread in order to create value.

While we insist that the companies we own have the potential to grow free cash flow over time driven by top line and bottom line results, we also emphasize sustainability over magnitude of growth. We reject the notion that a more rapid grower will by definition generate higher returns. We generally reject the very aggressive growth stocks, and we avoid the non-growers. Our sweet spot is predominantly the sustainable growers of earnings and free cash flow in the 5% to 25% range while emphasizing companies with a high level of existing and potential cash conversion abilities. It gets back to our emphasis on probability. The most aggressive companies are the most vulnerable to overvaluation, multiple fade, and competitive business pressures.

Bringing Valuation into the Equation

High growth stocks naturally trade at a forward Price to Earnings (P/E) premium, creating a dilemma for value conscious investors. Short-term valuation tools get too much attention but can be a tempting guide to quick investment decision-making for the lazy investor. The use of the words ‘cheap’ or ‘expensive’ are the most used misleading words in the investment world. The insightful article by Jeremy Siegel “The Nifty Fifty Revisited” from 1998, which supports our experience as well, suggests that current P/E valuations should not be a major concern, if deep fundamental research supports sustainability of growth.

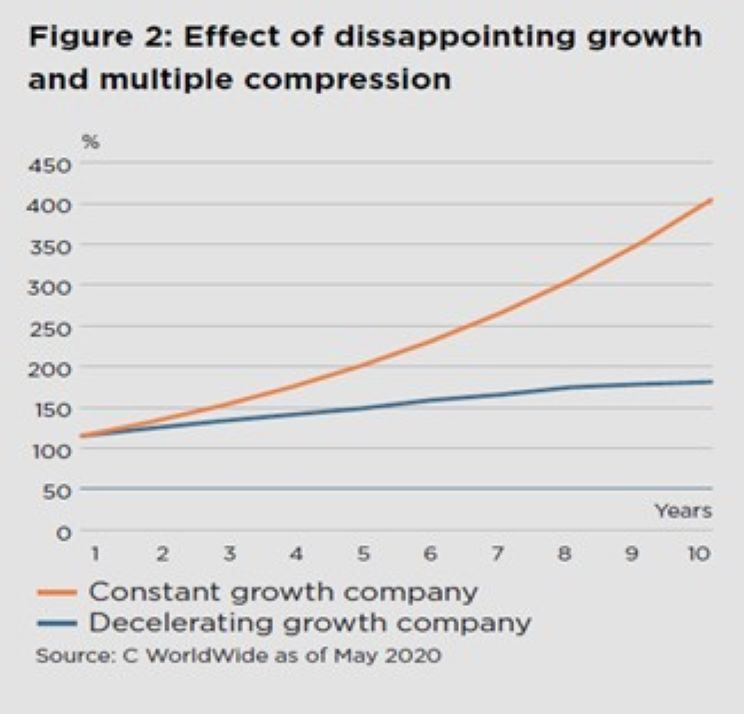

We spend most of our time focused on “what companies to own”, and less on “what to pay for them”. As such, we are not price driven investors. Valuation is a critical input in our decision-making process, but it is rarely, if ever, our starting point. Rather, valuation considerations typically only enter the discussion after all other aspects of the company have been analyzed. Our margin of safety has more to do with our confidence that a company’s competitive advantages will stay strong and or get stronger, rather than some estimate of a discount to intrinsic value. In our opinion, it is easier to be correct on the strength and longevity of the business model than the estimate of intrinsic value. We believe focusing on earnings potential rather than the valuation of the business not only focuses our minds on identifying potentially great companies but also helps to hedge capital over time. Figure 2, in simplistic terms, illustrates the point.

The chart shows two hypothetical companies which both start out growing earnings (cash flows) 15% per annum. The first company continues to grow 15% for 10 years, leading to an annualized return of 15% with a static P/E ratio. The second company sees decelerating earnings growth after year 1, and gradually falls back to an earnings growth of 10% pa, leading to a gradual (arbitrarily set) 40% P/E multiple compression over the 10 year period. While obviously the first company is the superior investment and, because of the reduced growth expectations for the second company, the initial high valuation goes against you. However, the investor still realizes an annualized return on the investment of 6% because the company continues to grow, albeit at a reduced pace. The important lesson to learn is that although the investor overpaid by 40%, the growth provided a buffer and safeguarded against an absolute capital loss.

At the end of the day, the key risk we seek to avoid, is a permanent loss of capital.

The Role of Valuation Over More Than 30 Years

Many of our successful investments have – on short-term conventional measures like P/Es – been considered by many as overvalued at the time of purchase. What happened was that the fundamentals unfolded with strong earnings and free cash flow growth which offset the effect of multiple compression. As an example, Alphabet has had periods of high valuation based on classic short-term metrics but has still historically compounded solid returns.

However, more often than not, we believe it is possible to invest in superior companies at attractive price levels, simply because the typical investor is either too short-term oriented or not willing to focus on the sustainability of growth and profitability. There is too much focus on static analysis and a belief that reversion to the mean is imminent. There seems to be a general urge to automatically fade the growth rates without consideration for the business and company differences. In a nutshell, that is our opportunity.

Company analysis involves numbers and financial ratios but even more importantly it necessitates a dynamic rather than a static evaluation of the companies and the themes that shape the world they operate in. It is a dynamic analysis that involves a continuous monitoring of the key drivers of long-term competitive advantages. Monitoring change and evaluating their effects with a rolling long-term (5 year) perspective and mindset. This is our methodology.

An example could be Visa as illustrated in figure 3, a company we analyze with the thematic view of a coming generational shift in payments from cash to digital. In 2011, one would pay 20 times 2011 earnings. Over the subsequent years Visa grew earnings 20% p.a. and the multiple has risen to 32.9 times 2020 earnings, a significant rerating. As a result, an investment in Visa has compounded at 26.4% p.a. over the period. Over the same period, the S&P 500 Index has compounded at 12.9%. As Visa has outperformed markedly the stock was far too cheap at purchase. But what would a rational long-term investor with perfect foresight have paid back then in 2011? What was the right P/E for a thematic compounder like Visa with consistent earnings growth and improving prospects supporting its multiple. What would have been the right price for a company that went on to grow (or compounded) EPS more than 4 times by 2019?

An investor with perfect foresight would have paid up to a price that would equalize the future total return with the return of the underlying market, in this case the S&P 500. That warranted price would be USD 65 equivalent with a P/E of 52 times 2011 earnings. At that price, the future total return of Visa would have been equal to the S&P 500 return over the subsequent 8 years. The lesson from this exercise is that you should pay up for growth and good business prospects, but also that growth stocks that are able to maintain earnings growth year-after-year are often worth many times more than what you pay for them and what consensus considers reasonable. This is because not only do you get the compounding from earnings growth, but you also receive the reward from multiple expansion.

Margin of Safety – Longevity of Competitive Advantage

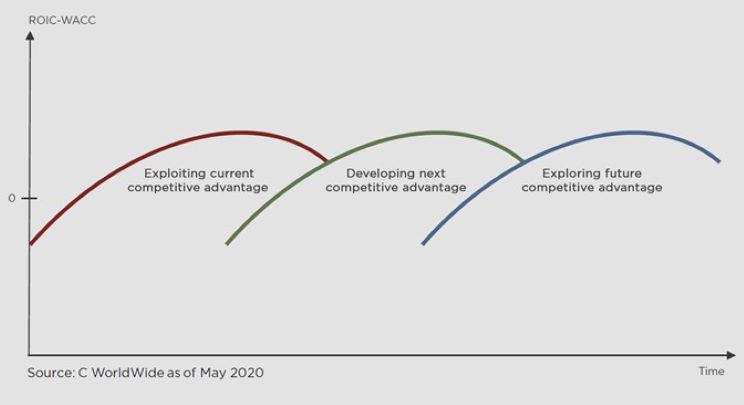

The importance of time is underestimated in financial markets. Compounding of earnings is linked to longevity of structural change. Obviously, a classic Net Present Value (NPV) calculation benefits from longevity – the longer you have thematic tailwinds the better – hence thematic tailwinds can justify higher short-term valuation multiples and reduce the risk of earnings disappointments. However, growth only has value if the company has a competitive advantage. It is hard to define the exact length of the competitive advantage period – the period a company can generate excess returns on its incremental investments. It is not a stationary analysis and has to be done with a dynamic long-term mindset. It is easier to evaluate whether the competitive advantages of the company on a rolling long-term (5 year) basis continues to be intact, weaken or strengthen. That is the key dynamic and task.

Companies that can sustain and extend their existing competitive positions and even build adjacent and new businesses because of financial strength and optionality in their business models are masters of their own destiny. These are the potentially attractive sustainable growers, namely, compounders. The extension of the length of a company’s competitive advantage can be exemplified as shown in figure 4 above.

Well managed companies that are able to generate significant excess returns have the opportunity to continuously create future competitive advantages by investing heavily – ahead of their competition, thereby creating a virtuous cycle of the strong getting stronger. These companies are often ignored by the short-term investor and a market with a 12-month focus and mindset, creating outsized return opportunities for the patient long-term investor.

The duration of competitive advantage for an individual company is driven by many factors which are challenged by the rate of industry change – if you are in a dynamic industry where market forces are changing quickly, the sustainability of competitive advantage tends to be shorter. It is our observation that the market tends to underestimate the sustainability of competitive advantage for thematically well-supported companies in less dynamic environments, and therefore underestimates the long-term compounding opportunity.

A good example of a compounder in a less dynamic environment that has been able to continuously create future competitive advantages, is Nestlé. Nestlé is the world’s largest food and beverage company, in existence since 1866 – founded five years after Italy unified – and has reported only one annual loss during its history, remaining in business throughout two world wars and the Great Depression. Nestlé’s operational performance may not look remarkable, but compounders do not require spectacular growth to outperform over time. Demand for the company’s products has been consistent, supported by constant innovation and product development, which has contributed to a perhaps unremarkable, but steady top line growth. With Nestlé’s high gross margins and a capital-light operating model, the result has been a resilient and steadily growing cash flow stream over time.

When it comes to finding compounders in more dynamic geographies like emerging markets, selectivity becomes even more important as companies face very different underlying conditions such as demographics, governance and the opportunity for a country to move up the value chain. Financial Services in India is such an opportunity. While financial services in developed markets can be a very complex area for stock picking, in a well-positioned country like India, the increase in the penetration of financial services and higher structural GDP growth have and should continue to benefit the Indian financial services company HDFC, provided continued strong execution.

Sustainability at The Core of Stock Selection

A shorter-term mindset to investing is often a reaction to events rather than preparing for them. With a very long investment horizon it pays to focus proactively on good business practices and Governance, not just to do less harm or to avoid risk but to fully understand the long-term merits of the company. As such, we have – long before ESG became what it is today – thought along the lines of sustainability, simply because we believe it is good for long-term returns. It evaluates what is material to all company stakeholders over a longer period than the next several quarters. In our view, the G in ESG should actually come first. It is the Governance factor that influences the E and the S, and the way that a company prioritizes its development in a world of constant change. Shareholders are therefore the first to benefit from a long-term approach.

Conclusion

It is said that Albert Einstein described compounding interest as the most powerful force in the universe. We firmly believe that the long-term trend in company earnings with high cash conversion determines the generation of returns, and that finding compounders is the holy grail of investing. The mindset of being on a constant search for compounders is a better use of time than exhausting one’s intellectual capital and time on trading in and out of stocks and segments of the market in a desire to look good in the short term. We have had a mindset of compounding at C WorldWide for three decades and it continues to be our mindset for tomorrow.

For more information, please access our website at www.harborcapital.com or contact us at 1-866-313-5549.

Important Information

Investing entails risks and there can be no assurance that any investment will achieve profits or avoid incurring losses.

This material does not constitute investment advice and should not be viewed as a current or past recommendation or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell any securities or to adopt any investment strategy.

The views expressed herein may not be reflective of current opinions, are subject to change without prior notice, and should not be considered investment advice.

Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) is a return ratio that expresses recurring operating profits as a percentage of the company's net operational assets.

The weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is the rate that a company is expected to pay on average to all its security holders to finance its assets. The WACC is commonly referred to as the firm's cost of capital.

Technology-media-telecoms (TMT) bubble is the fear of crystallising a loss, often forces investors and fund managers to hold onto a poorly performing stock longer than they should do.

A UNICORN bubble is a theoretical economic bubble that would occur when unicorn startup companies are overvalued by venture capitalists or investors.

The P/E ratio of the stock determines how much premium an investor is paying for a company's profits. Net present value, or NPV, is used to calculate the current value of a future stream of payments from a company, project, or investment.

3380685